When is the best time to register for a new GST/HST account? The answer to this question is every procrastinator’s dream: do it at the last minute.

For our purposes, the “last minute” is defined as “when you reach the $30,000 sales threshold limit”. If you exceed $30,000 in sales of taxable supplies in a single calendar quarter, or within the previous four calendar quarters combined, you are required to charge GST/HST and register for a GST/HST account.[1]

If you have not reached the $30,000 threshold, you can voluntarily become a GST/HST registrant. However, as detailed below, there are three strong arguments as to why you should not volunteer.

There’s no financial benefit to volunteer (with some exceptions)

Unless your expenses are greater than your revenues, there’s no financial benefit to voluntarily register for a GST/HST account. That is because you will almost always pay more in “total taxes” as a GST/HST registrant compared to a non-registrant.

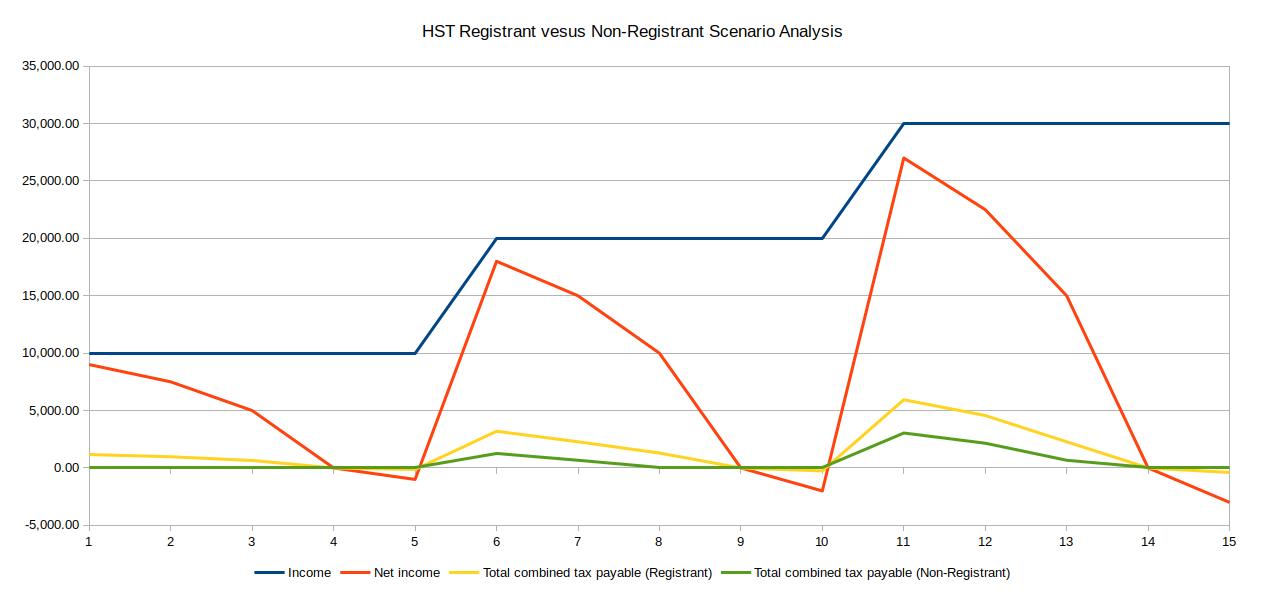

To illustrate this point, let’s examine three levels of income between $10,000 and $30,000 with five scenarios of expenses at ratios of 10%, 25%, 50%, 100%, and 110% of income (see Graph 1, below). On the X-axis, the $10,000 income level is represented as numbers 1-5, the $20,000 income level as numbers 6-10, and the $30,000 income level as numbers 11-15.

Income beyond $30,000 is not considered as, at that threshold, you are required to register for a GST/HST program account.

Graph 1 – HST Registrant versus Non-Registrant Scenario Analysis

At X-axis point 1, income is $10,000 and expenses $1,000 leaving a net income of $9,000, which results in a total combined tax payable of $1,170 for the GST/HST registrant.[2] In the same scenario, a non-registrant would be financially better off with a total combined tax payable of zero.

From X-axis points 1-4, Graph 1 shows the effect of gradual increases in expenses relative to the $10,000 income level. At X-axis point 4, net income is zero represented by $10,000 of income and $10,000 of expenses. With net income of zero, both the registrant’s and non-registrant’s total combined tax payable is nil. Therefore, all things considered, being a registrant or non-registrant is irrelevant if your net income is zero.

As may be expected, the variance between the total combined tax payable of the registrant and non-registrant increases at the $20,000 and $30,000 income levels. For example, at X-axis points 1, 6, and 11, all representing a 10% ratio of expenses to income, total combined tax payable for the GST/HST registrant is $1,170, $3,194, and $5,939 – compared to zero, $1,264, and $3,044 for the non-registrant. In all income scenarios, the non-registrant is financially better off when their income is greater than their expenses.

Only at X-axis point 5, where expenses exceed income by 10%, does being a GST/HST registrant provide greater financial benefit. Here the registrant receives a HST refund of $130 – a refund on the amount of expenses that exceed income ($1,000 x 13%). In comparison, the non-registrant has a total combined tax payable of zero. Similar results are derived from the other two income and expense scenarios as well. At X-axis points 10 and 15, also representing a 110% ratio of expenses to income, the GST/HST registrant would receive refunds of $260 and $390 whereas total tax payable for the non-registrant is zero.

In summary, there are three rules to take away from our analysis:

- the non-registrant is better off when income is greater than expenses;

- being a registrant versus being a non-registrant is irrelevant when net income is zero; and,

- the registrant is better off when expenses exceed income.

Extensions of “Rule 3”

There are two main extensions of the third rule, which states that “the registrant is better off when expenses exceed income”. As detailed below, the first extension considers purchases of capital assets, and the second takes into account income generated from “zero-rated” taxable supplies.

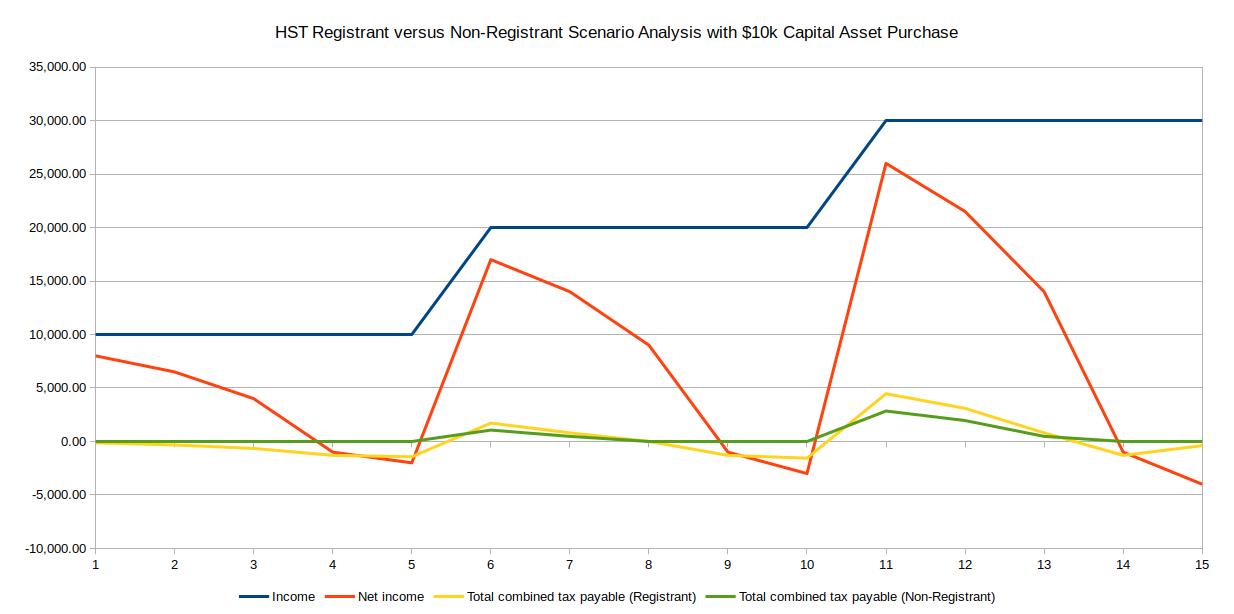

Let us begin with the first extension of Rule 3. We previously demonstrated how GST/HST registrants are better off in scenarios where expenses exceed income: a result of excise tax refunds generated from expenses in excess of income. We now extend this conclusion to illustrate that registrants are also comparatively better off when the sum of expenses and capital purchases exceed income.

Graph 2, below, expands on the three income-level and five expense-level scenarios previously examined in Graph 1 by adding in the net tax effect of a $10,000 capital asset purchase.

Graph 2 – HST Registrant versus Non-Registrant Scenario Analysis with $10k Capital Asset Purchase

Graph 2 illustrates that net income in the asset purchase scenario is only marginally less than that calculated with no capital purchases (see Graph 1, above). That is because capital purchases must be incrementally expensed – or amortized – under the Capital Cost Allowance (“CCA”) framework of the tax system: Canadian tax law does not permit capital purchases to be written off entirely in the year of acquisition.

In this new scenario, if we consider income tax alone, the registrant and non-registrant are on equal footing. However, once GST/HST enters the picture, we find that the registrant may deduct the entire amount of GST/HST paid on their excise tax return in the year of acquisition whereas the non-registrant has no such option and must incrementally amortize GST/HST paid using the CCA framework.

In other words, unlike the income tax return, there is no discrimination between an expense or a capital expenditure on the GST/HST return: the registrant claims the HST of $1,300 paid on the asset in the year. In this scenario, the registrant is better off. As long as total expenses plus asset purchases exceed income, the registrant will always expend more GST/HST than they collect and, therefore, benefit from an excise tax refund. The non-registrant, on the other hand, receives a 13% greater CCA deduction per year and no immediate GST/HST refund.

Given a $10,000 capital asset purchase, the results in favour of the registrant are exaggerated at the $10,000 income level and non-existent at the $20,000 and $30,000 income levels. For example, at the $10,000 income level, a registrant would receive refunds of $130, $325, $650, $1,300, and $1,430 at expense ratios of 10%, 25%, 50%, 100%, and 110%, respectively, whereas a non-registrant would have total combined tax payable of nil in all five expense scenarios.

On the other hand, at income levels of $20,000 and $30,000, the non-registrant is better of at the 10% and 25% expense levels, indifferent at the 50% level, and – in accordance with our earlier findings – the registrant is better off at the 100% and 110% expense levels. The reason why is simple: these are the scenarios where the sum of expenses and capital purchases exceed income.

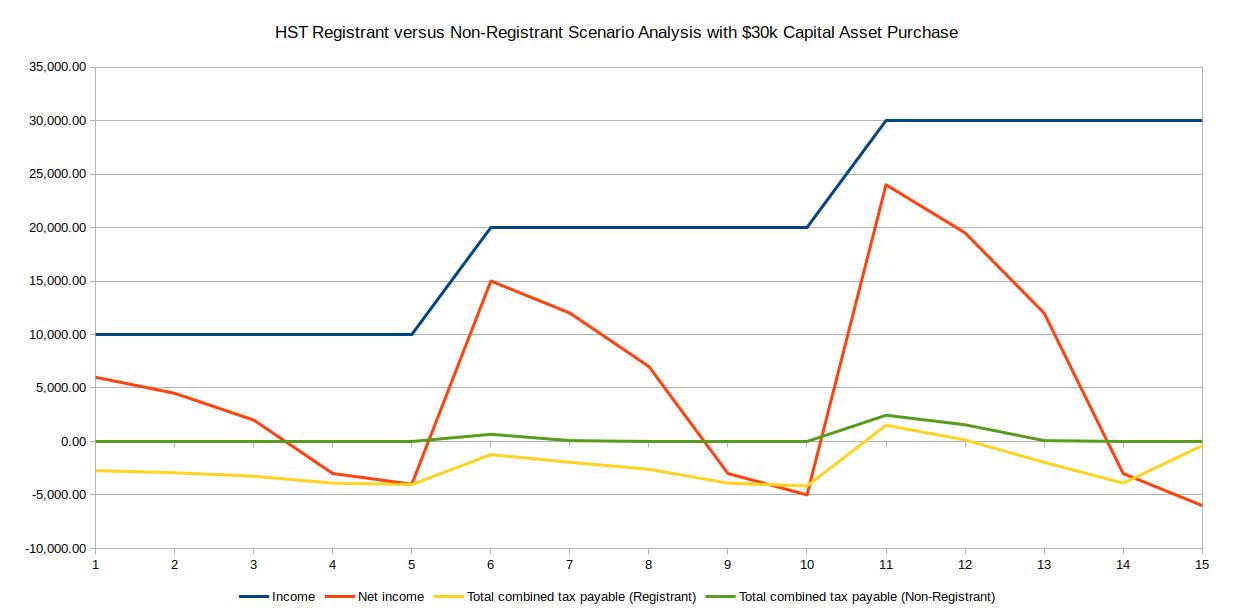

In the case of a $30,000 capital asset purchase, the sum of expenses and capital purchases would exceed income at all applicable income levels. Therefore, excise tax refunds would be several factors larger than the results illustrated in Graph 2 making the registrant financially better off in all scenarios (see Graph 3, below).

Graph 3 – HST Registrant versus Non-Registrant Scenario Analysis with $30k Capital Asset Purchase

With a $30,000 purchase, increased amortization expense deductions have a larger impact on net taxable income and, therefore, income tax of both the registrant and non-registrant. However, any reduction in income tax for the non-registrant is greatly overshadowed by the large excise tax refunds generated in favour of the registrant, a benefit the non-registrant will see no part of.

Given the findings in the capital asset scenario analysis above, we may extend our third rule to include the registrant is better off when GST/HST expended is greater than GST/HST collected.

Zero-rated supplies

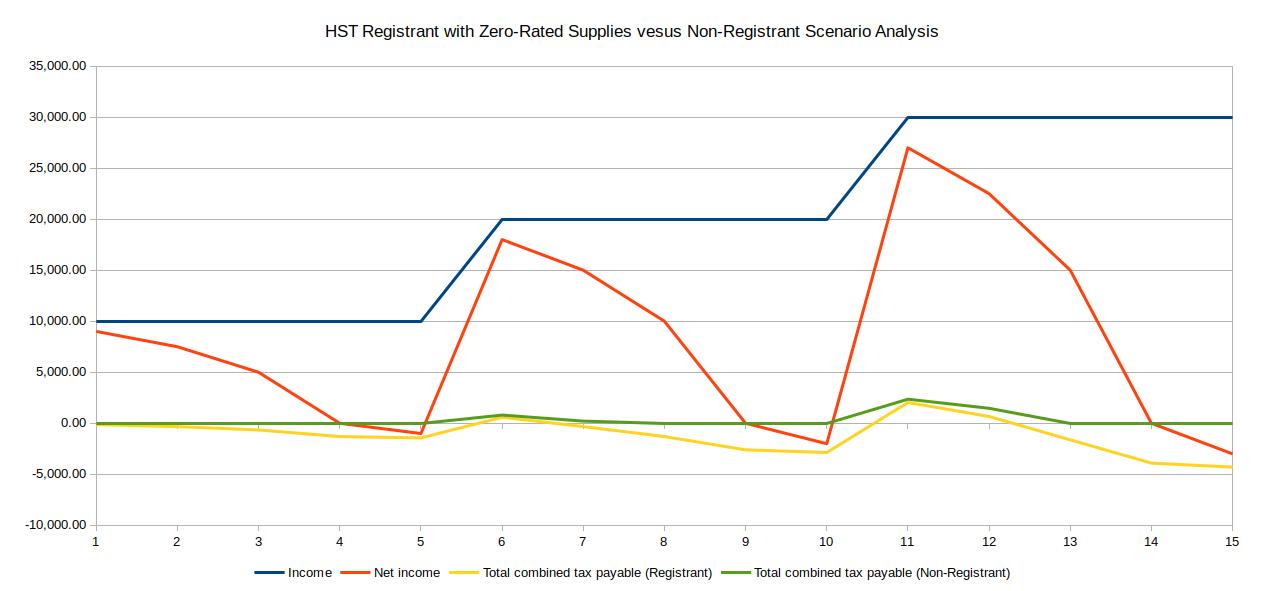

Our second extension of “Rule 3” concerns businesses selling zero-rated supplies. Such businesses do not charge or collect GST/HST on their taxable supplies, but are permitted to recover excise taxes expended when filing their periodic GST/HST returns. Examples of zero-rated businesses include those in medical services (general practitioners, dentists, and opticians), those selling basic groceries or agricultural goods, and exports.[3]

Given that our refined Rule 3 states that the registrant is better off when GST/HST expended is greater than GST/HST collected, it is easy to comprehend why a business selling zero-rated supplies would be better off as a registrant versus as a non-registrant. The reason is simple: a registrant selling zero-rated supplies will always expend more GST/HST than they will collect – as they will always collect zero GST/HST.[4]

Graph 4, below, compares the total combined tax payable of a zero-rated registrant to a non-registrant using our previously analysed income and expense levels.

Graph 4 – HST Registrant with Zero-Rated Supplies versus Non-Registrant Scenario Analysis

With expenses equal to 10% of income, a registrant will incur total combined tax payable of -$130 (refund), $594, and $2,039 at the $10,000, $20,000, and $30,000 income levels whereas the non-registrant will incur amounts of zero, $808, and $2,361. The benefit to the registrant becomes more apparent when expense levels are equal to income, or greater. For example, at net income of zero the registrant will receive GST/HST refunds of $1,300, $2,600, and $3,900 as compared to the non-registrant’s total combined tax payable of nil.

Scenario analysis aside, there are two additional points to consider before voluntarily registering for a GST/HST program account: the concept of “deemed trust amounts”, and account administration costs.

It’s a trust account

A balance owing on a GST/HST program account is not considered a personal or corporate debt. In fact, GST/HST amounts collected are considered deemed trust amounts collected on behalf of the government.

When it concerns the collection of excise tax, there are many reasons why the distinction between a debt and a deemed trust amount is important. For a registrant, for instance, there is a primary risk: if trust amounts are not paid on time, the CRA has numerous tools at their disposal to collect including seizing bank accounts, garnishing wages, issuing requirements to pay to customers, seizing and selling assets, and securing liens on property. With debts, the CRA has similar tools, but collection actions are typically slower to materialize.

Concerning corporations, directors of corporations with outstanding trust amounts may face CRA claims of directors’ liability, making the directors personally liable if the company is not able to pay. This is contrasted with corporate tax debt, which is the corporation’s liability and not typically recoverable from the directors.[5]

Another distinction between a trust amount and debt is, when a taxpayer appeals a tax assessment, the CRA cannot collect the amounts under appeal; however, concerning trust amounts, there is no such latitude when appealing excise tax assessments – the amounts are immediately collectible.

Businesses considering voluntarily registering for a GST/HST program account should fully understand the risks and responsibilities inherent in maintaining such an account. All risks can be eliminated by not voluntarily registering in the first place.

Accounting, administrative, and potential audit costs

The final point to consider in deciding whether to voluntarily register concerns accounting, administrative, and CRA audit costs. Registrants require additional accounting to track GST/HST collected and expended, and to file periodic excise tax returns. Additional accounting translates into the outlay of additional time and/or money, which may amount to several hundred or several thousands of dollars per year depending on the business’s operations and accounting fees.

Furthermore, if the business’s GST/HST returns are selected for audit by the CRA, the business may also incur additional accounting or legal fees if professional advice or assistance is required. In conclusion, businesses should consider all costs related to administering the excise tax account, as administrative costs may outweigh financial benefits in certain scenarios.

Footnotes

- For more information see https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/tax/businesses/topics/gst-hst-businesses/register-a-gst-hst-account.html

- The $1,170 total combined tax payable is made up of $1,300 HST collected on $10,000 of sales, and $130 of HST disbursed on $1,000 of expenses. The resultant calculation being $1,300 minus $130 (input tax credits) equals a net tax refund on the GST/HST return of $1,170. Personal income taxes are nil at this income level and, therefore, do not increase total combined tax payable.

- Zero-rated suppliers should never be confused with exempt suppliers who do not charge or collect GST/HST on their exempt supplies, and are not permitted to recover excise taxes expended on the creation or provision of such supplies.

- The only exception being that, when a registrant with zero-rated supplies sells a capital asset, they are required to charge GST/HST on the sale of the asset.

- However, for director/shareholders be aware of liability issues that may arise from issued dividends or shareholder appropriations, etc.